By Omar. S.Mahmood

April 27th, 2016

On April 1st, Nigerian security forces in the central state of Kogi arrested Khalid al-Barnawi, a prominent jihadist figure and presumed leader of the Boko Haram offshoot Ansaru. Despite uncertainty regarding his recent status, Barnawi’s detention is one of the more substantial in the course of Nigeria’s battle against Islamic militancy, and has already began to bear fruit with the arrest of his deputy twelve days later. At the same time, the event also raises questions regarding Ansaru activities in the three years since its last major attack, and its status vis-à-vis Boko Haram.

Khalid al-Barnawi

Barnawi is a pseudonym for Usman Umar Abubakar, a mid-40s militant from Borno state who served as a founding member of Boko Haram. Barnawi reportedly trained with Al Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) in Algeria, maintaining “close” links with Mokhtar Belmokhtar and the organization thereafter. Following his return to Nigeria, Barnawi planned kidnapping operations against foreign nationals, and was allegedly involved in the 2011 bombing at the UN headquarters in Abuja, among other violence. Barnawi was linked to Ansaru’s emergence in January 2012, and following the March 2012 death of founder Adam Kambar, who had also trained Algeria, Barnawi emerged as the sect’s new leader.

Barnawi’s preeminent status as a dangerous militant was reinforced by his inclusion on a “Most Wanted” list put out by the Nigerian military in November 2012, which categorized him a Boko Haram Shura Council member despite the January advent of Ansaru. The United States also labeled Barnawi a “Specially Designated Global Terrorist” in June 2012, which was later accompanied by a five million dollar reward. In both cases, Barnawi was listed in a tier just below Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau, an indication of his position within Nigerian jihadist circles.

Despite his stature, Barnawi’s role as the time of his arrest is unclear. Ansaru distanced itself from Boko Haram for a number of reasons, paramount of which was a lack of tolerance regarding Muslim casualties. Ansaru messaging referenced this as a grave sin, and fliers announcing the group’s formation surfaced immediately after the January 2012 assault on Kano, which killed nearly 200. In contrast, Ansaru operations comprised of a series of Western nationals kidnappings, an attack on a high-security prison in Abuja, and an assault on a Nigerian military convoy on its way to deploy in Mali, demonstrating a limited focus on international targets and Nigerian security institutions.

Nonetheless, Ansaru largely went quiet in 2013, with its last major kidnapping operation in February. Given Barnawi’s ties to AQIM, it was assumed that French intervention in northern Mali disrupted such links, hindering Ansaru’s capabilities. Forcing Ansaru into a tough position, a 2014 report from the International Crisis Group citing interviews with Ansaru members, noted that this led to Ansaru’s reintegration into Boko Haram, smoothed over by Shekau’s selection of Barnawi disciple Babagana Assalfi as his deputy. The advent of Boko Haram kidnapping operations in northern Cameroon signified the newfound cooperation, and despite Assalafi’s death in Sokoto state during a raid in March 2013, the agreement may have held up, helping explain Ansaru’s relative operational quiescence thereafter.

While Barnawi may had participated in a rapprochement with Boko Haram, at least a small faction of Ansaru remained outside any agreement, unable to reconcile with an organization that continued to kill Muslims. Ansaru messaging chastised Boko Haram for attacks such as a September 2013 massacre along a highway near Benesheikh where over 140 motorists were killed, and offered condolences to the victims of a blast that resulted in the death of approximately 100 worshippers at Kano’s central mosque in November 2014. As Boko Haram attacks on civilians became bolder, so too did the messaging on the subject, with two videos in early 2015 specifically denouncing Boko Haram’s “ideology,” which involves “attacks on mosques, markets, bus stations, and other places.” In this sense, the central tenet behind Ansaru’s separation from Boko Haram remained unresolved, preventing a portion from seeking any sort of reconciliation.

While Ansaru did not conduct any more headline grabbing attacks, militants were involved in a few operations in the central areas of Nigeria, demonstrating that a small group remained operationally active. For example, in June 2014 the Nigerian Army announced the death of a likely Ansaru member after a confrontation in Plateau state, while a January 2015 Ansaru video discussed a battle with Nigerian security forces in the village of Mundu, Bauchi state.

In addition, other locations in Nigeria’s central areas experienced Ansaru-like attacks, which largely went unexplained. Kogi state in particular, the location of Barnawi’s arrest and the attack on pre-deployment troops, suffered from violence directed at security institutions in late 2014 and again in September 2015. This largely coincided with a period in which Boko Haram’s focus lay in maintaining territorial control in the northeast, resulting in an overall contracted attack radius. Officials blamed the incidents on criminal elements, but one targeted soldiers traveling to a counterterrorism training along the same road as the 2013 incident, while others were directed towards a police station, the Department of State Services (Nigeria’s domestic intelligence agency), and freeing inmates from a previously-targeted prison, utilizing dynamite and twenty gunmen.

More recently, a sequence of arrests of reported Ansaru members, including a seven-member cell in Katsina that was in the attack planning stage in January 2016 and a set of three in Kaduna in March 2016, may have provided information that led to Barnawi’s capture. The first group was reportedly linked to the Islamic State, while the second was planning to travel to Sudan for training, underscoring Ansaru’s continued international connections.

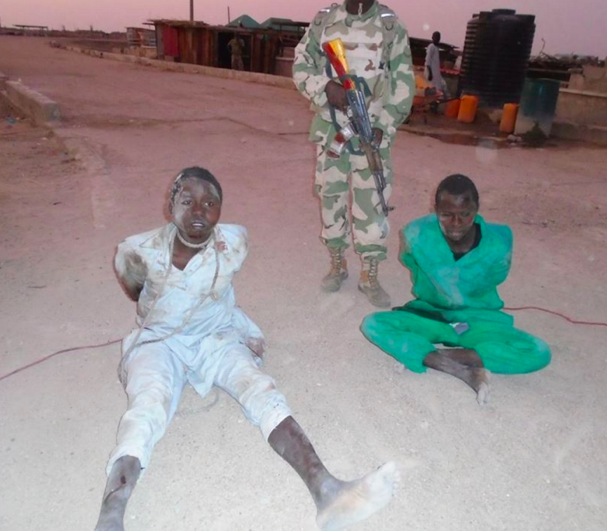

Two suspected militants arrested in northern Borno state. Photo credit: Nigerian Army.

Barnawi’s role in all this is opaque, and whether he remained the leader of an Ansaru faction continuing the group’s original ideals in opposition Boko Haram violence, fully reintegrated within the structures of Boko Haram, or managed a careful balancing act between the two is unknown. The location of his arrest in Kogi would suggest at a minimum, that he was not involved in day-to-day intricacies of Boko Haram’s battle in the northeast, and may have played a role in the violence more local to him.

Regardless, the arrest of a prominent militant is a crucial success story for the Nigerian Government, and a reminder that Islamic militancy is not necessarily confined to the northeast. It also helps curtail external linkages between Nigerian militants and those based in northern Mali, by removing a key interlocutor. Nonetheless, while Barnawi’s arrest is important, given his distance it is unlikely to make a noticeable dent in Boko Haram operations, while its lasting effects on the frayed remnants of a once briefly potent Ansaru remain to be seen.

Omar S. Mahmood is an analyst focused on the Lake Chad and Horn of Africa regions, and can be reached on Twitter @omarsmahmood.